Zur Erinnerung an 1020 G-PWW-Coy Shooters Hill – As a Memento of German Prisoner of War Working Company 1020 Shooters Hill – is the title of an exquisite, slim booklet from the archives of the Greenwich Heritage Centre. Its contents are a set of pen and ink drawings of the PoW camp by one of the German prisoners, Wolfram Dörge. Dated Christmas 1946, it is dedicated to the officer in charge of the camp, Major Leech, who was known to the prisoners of war as the “Father of the Camp”.

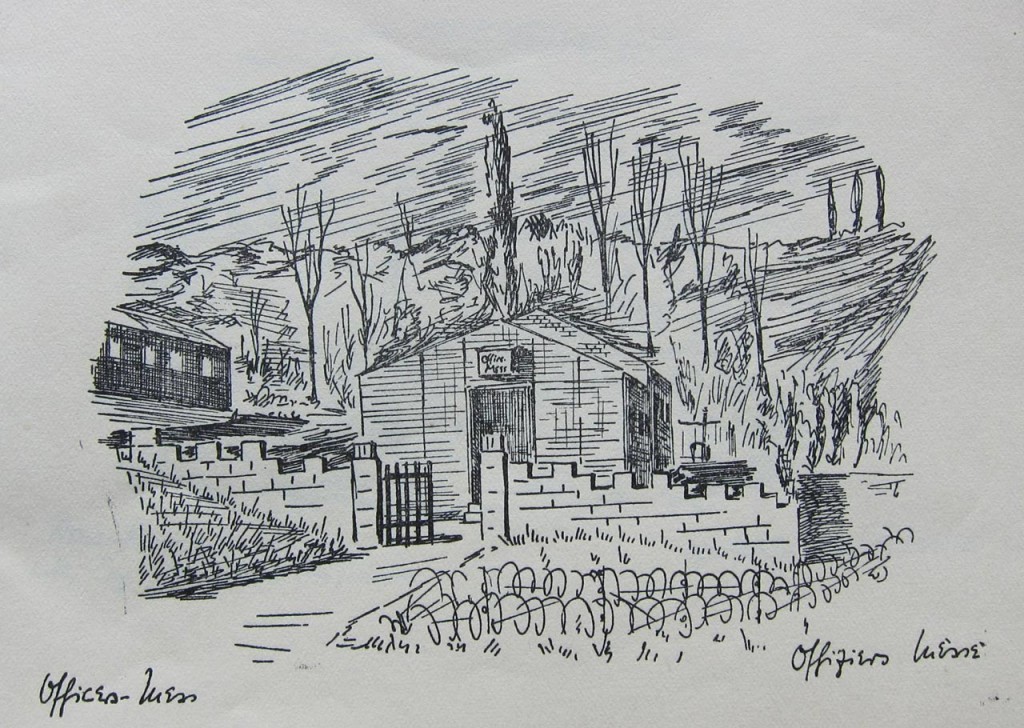

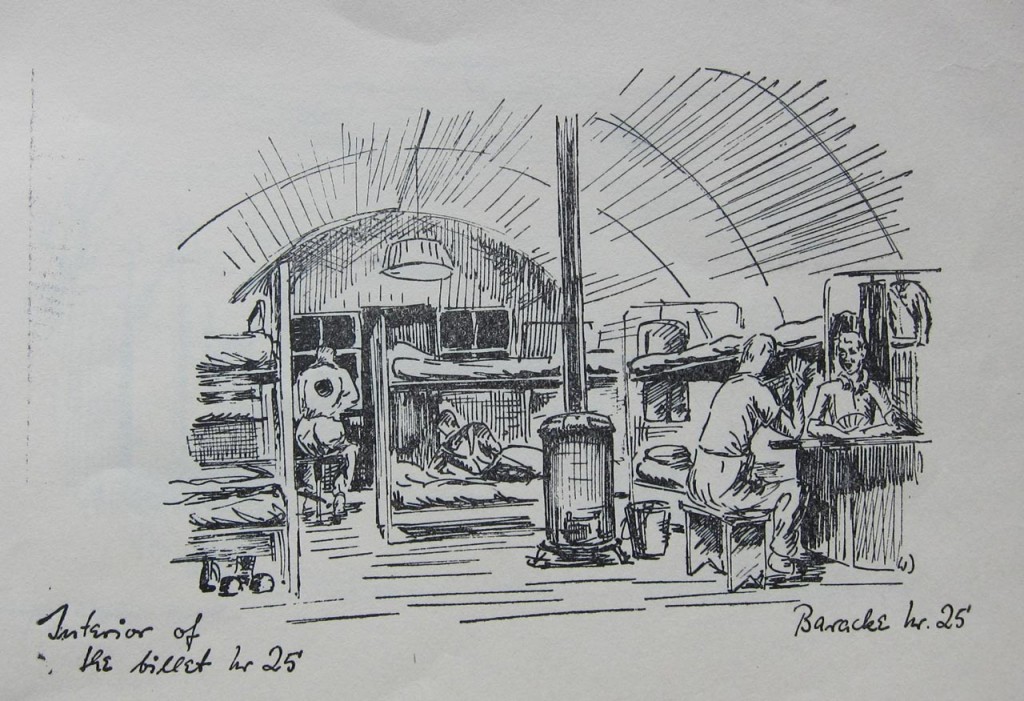

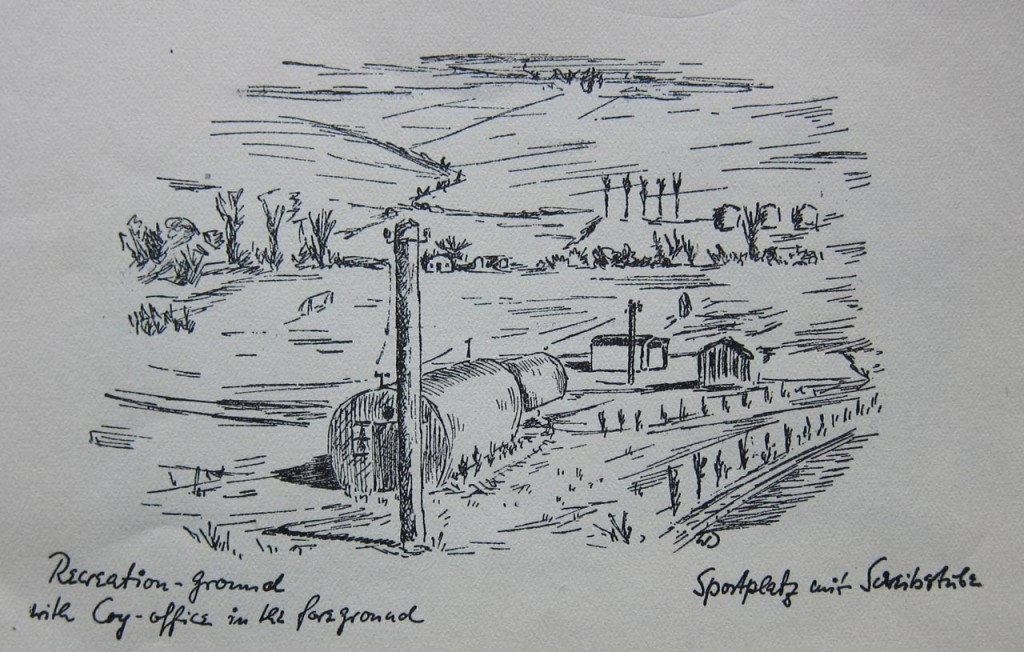

Wolfram Dörge’s pictures show the various huts that made up the camp, including the mess hut, the infirmary, the recreation room and the cobblers’ and tailor’s shop. They also include views of the inside of some of the huts, such as the billet hut shown below, the kitchen and the stage in the recreation room. It is a unique record of life for German prisoners of war in the UK after the end of the second world war.

The camp was situated in the area now taken up by the southernmost 9 holes of Shooters Hill Golf Club, the part nearest Shooters Hill, plus the westernmost fields of Woodlands Farm. The Shooters Hill Golf Club history page summarises the use of this part of the course during the war years:

In 1939, the southernmost 9 holes of the course were requisitioned for the establishment of an anti-aircraft battery and part of the Clubhouse became the headquarters of the Home Guard, and in the latter years part of the course also became a Prisoner of War camp for some 1000 German and Italian prisoners. The camp was surrounded by a 7ft high wire fence, and the cookhouse situated by the 17th green. The remaining 9 holes continued to be played even though the course sustained considerable damage from bombing.

The anti-aircraft battery was an unusual one – it was a Z Battery, which used 3-inch rockets to defend against enemy air attacks. In 2005 a community archaeological research programme called the “Lie of the Land project” led by local archaeologist Andy Brockman investigated the Shooters Hill ZAA Battery and the findings are documented in chapter 14 of Images of Conflict: Military Aerial Photography and Archaeology. An aerial photograph of the golf course from August 1944 shows the 64 twin-barrelled rocket projectors of the battery arranged in an 8 by 8 grid across the eastern-facing slopes. The battery was initially manned by personnel from the Royal Artillery, but later the Home Guard took over and it was fully manned by the Home Guard from the end of July 1943.

Even at the time it seems there was some doubt about the effectiveness of such unguided rockets against enemy aircraft, and it was suggested that they were there as much for civilian morale as for usefulness in defence. After the battery was stood down it is reported that the Mayor of Bexley sent a message to the stand down dinner which included the comment: “Thank God you are standing down because you have caused more damage to property in Bexleyheath than the enemy has”.

The Z Battery was on the golf course between August 1942 and November 1944, according to David Lloyd Bathe’s “Steeped in History”, which also mentions that an American tented camp was there before the PoW camp. Another aerial photograph from Images of Conflict, from October 1945, shows rows of military Bell tents which were no longer there in the autumn of 1946 – presumably this was the American camp – though when the PoW camp was first set up some of the prisoners were billeted in tents.

Camp 1020 was formed on 26th June 1946 according to a fascinating document from the National Archive which was referred to by Andy Brockman in his talk about the camp to Shooters Hill Local History Group last September. Andy thanked SE9 Magazine who passed on the document which is a report on an inspection visit to the camp and gives details of the PoWs and their educational and cultural activities in the camp, including the work to “denazify” the prisoners .

At the time of the report there were 533 German prisoners in the camp. They had all been transferred from Camp 197 at Chepstow, but before that 75% had been in the USA and the remainder in Belgium. Initially morale was low, as the report says:

Morale at first was low, owing to the disappointment of Ps.W. ex USA, who had been assured by American officers that they were being repatriated, and discontentment of Ps.W. ex Belgium who alleged they had been badly fed and roughly treated in Belgium. Good treatment, attention to welfare and educational activities on the part of the British staff and better food has now raised morale considerably. Many Ps.W. ex Belgium have gained up to 40 lbs in weight and the camp can now be regarded as content and happy.

Many of the activities organised for the prisoners were aimed towards political re-education, or denazification. One of the first steps was to classify how strongly each prisoner adhered to the Nazi ideology. A report on a project about another PoW camp, at Butcher Hill in Horsforth, explains the classification scheme:

White patches (‘A’ ‘A-‘) were for prisoners with no loyalty or affiliation to the Nazis. A grey patch (‘B+’ ‘B’ ‘B-‘) meant that the prisoner, although not an ardent Nazi, had no strong feelings either way (mitläufer). Hard-core Nazis and almost all Waffen SS and U-Boat crews wore a black patch (‘C’ or ‘C+’).

It isn’t clear whether the black/grey/white patch system was used at Camp 1020, but the camp was classified overall as grey and the A/B/C method of classifying prisoners was used. The vast majority of Shooters Hill prisoners were classified as A and B with just 31 Cs and 1 C+.

There were a wide range of re-education activities, including lectures on “Public Life in England” and “Germany yesterday, today and tomorrow” which were attended by between 100 and 150 prisoners and were followed by “lively discussions”. A press review was held three times a week attended by 150-200 men. Press items were selected and translated beforehand for the review. “Mr. Churchill’s speech at Conservative Conference was given in full and caused much discussion”. The radio was popular, with about 200 men listening to the BBC news in German on the “good quality wireless” in the recreation room. The YMCA Film Unit visited every Tuesday.

There were beginner, intermediate and advanced classes in English and classes in French and Spanish. The number of classes was limited by lack of accommodation, according to the report. It also recommended that the library of 103 books in German and 100 in English be augmented with more German novels. In addition the supply of newspapers needed to be increased. They received copies of the Daily Express, Daily Herald, Daily Mail, the Times and the News of the World, and also of a UK government produced newspaper in German called Wochenpost. The 50 copies of the latter were deemed totally inadequate for a camp of 530 men.

Why were prisoners of war still held in 1946, when the war in Europe had ended over a year earlier? They were kept as workers to help in reconstruction work at a time when many British workers were still overseas in the armed forces. Under the Geneva Convention PoWs couldn’t be forced to work, but most of them volunteered to as a way of passing the time. At its peak in September 1946 there were 402,200 prisoners of war in the UK, in hundreds of camps, of which 84.9% were working. It has been estimated that 25% of the workforce in the UK was such PoW labour.

“Steeped in History” records that the prisoners in Camp 1020 worked mainly in the warehouses of the North Woolwich dockyards and in the public utilities of military and civilian facilities. A few helped with farm work, for example harvesting potatoes at Woodlands Farm where the Western field was given over entirely to growing potatoes. They also worked on the groundworks for the Cherry Orchard Estate in Charlton and on snow clearance in the harsh winter of 1946/47. David Lloyd Bathe tells the story of how they saved a Charlton football match:

In the very severe winter of 1946/47, PoWs volunteered to clear the snow from the First Division Charlton Athletic’s football ground so that a regular weekend game could be played. About 300 PoW volunteers were “guests of honour! at the game.

“When our part in saving the game was acknowledged over the loudspeakers, there was much cheering and backslapping, and many cigarettes came our way!”

Prisoners at the camp were allowed quite a lot of freedom. When they weren’t working they could move freely within 5 miles of the camp in daylight hours. On Sundays a party of about 70 protestants went to a service in Welling Church. Catholics initially had a religious service at the camp led by a German speaking priest, but later they attended a mass arranged by Fr. Nevatt at St. Stephen’s RC Church in Welling. This became known to parishioners as the German Mass and hymns were sung in German.

According to David Lloyd Bathe the prisoners at Working Camp 1020 were discharged from the camp in the spring of 1947. Now, nearly 70 years later, almost all trace of the war-time uses of the golf course and farm has disappeared. Apart from some anomalies in archaeological geophysical surveys at Woodlands Farm all that remains is a couple of ramps leading from Shooters Hill towards the golf course.