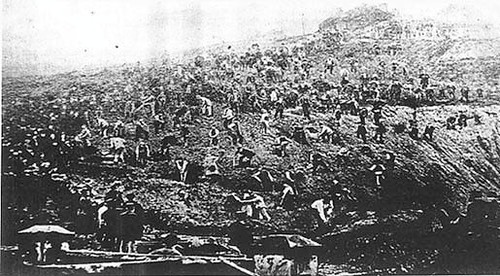

The 1876 riot that apparently saved Plumstead Common from enclosure, in the photo the people are digging up the enclosing fences (apparently).

Having recently run into something of a copyright challenge it was quite nice to pick up a book that has the following announcement inside its front cover: “Please reproduce, spread, use all or part of this text (so long as it’s not for anyone’s personal profit), but we’d like to know you are doing so.” The text that’s about to be reproduced, spread and used on this site was originally put together by past-tense publishing, and investigates a number of historic events connected to the preservation of green space in South London, including the one below: a riot that prevented the enclosure of Plumstead Common.

“A Series of Wild and Violent Riots”

Plumstead Common belonged to the Provost and Scholars of Queens College, Oxford. Freehold tenants had enjoyed rights of cattle-grazing, and collection of gravel, turf, loam etc for centuries. It was a wild and picturesque place, loved by locals, especially kids. Troops had been allowed to exercise here in the 19th Century, leading to “the present ruinous condition of the remoter half” (WT Vincent). In 1816 two plots of land were enclosed where Blendon Road and Bramblebury Road are now. In the 1850s an area between The Slade and Chestnut Rise was sold. There were “distant rumblings” in Parish meetings, but no more. Some small plots enclosed on the fringes of the Common were given to poor widows to keep them out of the workhouse, according to Vincent (more to cut expenses to the ratepayers than from generosity possibly). From 1859 however, the College aggressively pursued a policy of excluding freeholders, asserting they were practically the owners of the waste land. Various encroachments were made, reducing the Common by a third: in 1866 the whole of Bostall Heath and Shoulder of Mutton Green were enclosed.

This led to local outrage, meetings of residents of East Wickham, and the forming of a protest committee, led in March 1866 to the forcible removal of the fences around the Green, and also destruction of fences near the Central Schools around Heathfield and Bleakhill. In a legal challenge by Manor tenants to the College, the Master of the Rolls ruled the enclosures on the Common and Bostall Heath out of order.

“A party of women, armed with saws and hatchets”

‘Illegal’ encroachments continued though – often facing unofficial demolition by locals. The Plumstead Vestry even passed motions in favour of the demolitions! The main targets were the property of William Tongue, a rich local builder who had bought the land here and put fences up, & his crony, magistrate Edwin Hughes, Chairman of the Vestry (later Tory MP for Woolwich). Hughes was said to have “had the key to the Borough in his pocket” -a very powerful man locally. He had bought land off Tongue to add to his garden. Tongue had already been the focus for trouble in 1866 over his enclosing ways. On a Saturday in May 1870, “a number of the lower class, who were resolved to test their rights” demolished fences and carried off the wood. “A party of women, armed with saws and hatchets, first commenced operations by sawing down a fence enclosing a meadow adjoining the residence of Mr Hughes…” Fences belonging to William Tongue were pulled down. There was talk of pulling down Hughes’ house as well. Hughes called the coppers, and some nickings followed. The next day 100s of people gathered and attacked fences put up by a Mr Jeans. When the bobbies arrived many vandals took refuge in the local pubs.

From 1871, the military from nearby barracks took over large sections for exercises and drilling, as Woolwich Common was too small and swampy: the squaddies soon trashed the place, stripping all the grass and bushes and brambles. Protests followed, but nothing changed.

In 1876, Queens College decided to lease the greater part of the common permanently to the army for extensions to the Woolwich Barracks/parade grounds. Local people, including many workers from Woolwich Dockyard, objected to the plans; notices appeared around the town in late June calling for a demonstration. The main organiser of the demo was John de Morgan, an Irish republican & agitator, who had been involved in struggles against enclosures in Wimbledon (in 1875) & Hackney. De Morgan seems to have been a charismatic (or self-publicising) and provocative figure, a freelance editor, orator & teacher, who had been driven out of Ireland for trying to start a Cork branch of the International Workingmens Association (the First International). He had long been a Secularist and Republican, but fell out with some radicals and other Secularists. He had founded a Commons Protection League.

“I Never saw a Scene So Disorderly and Lawless”

On July 1st over 1000 people held meetings in the Arsenal Square and the Old Mill pub, marched up to the north side of the Common (around St Margaret’s Grove) and peacefully tore down fences. Again fences belonging to Edwin Hughes and William Tongue were destroyed – the crowds now had added grudges against them. Both had recently been involved in crushing an 1876 strike by local carpenters and bricklayers over pay and piecework, making then doubly hated. Tongue had brought in scabs to break the strike and Hughes prosecuted strikers for leaving work (under the notorious Employers and Workman’s Act.) A widely disliked Mr Jacobs, who leased a sandpit off the College, also had fences broken.

The following day (Sunday) a crowd returned to demolish the already rebuilt fences: a police attack led to a battle with stones thrown and fires started. Monday saw more rioting: according to a hostile witness there were 10,000 there on Monday and Tuesday, and “I never saw a scene so disorderly and lawless.” The furze on Tongue’s land was set on fire. While the cops brought it under control, enthusiastic meetings continued.

Although many rioters were costermongers, local coalheavers, labourers from the Woolwich Arsenal (700 men took the day off from one department here to hear a de Morgan speech), many more ‘respectable’ workmen were up there trashing the fences.

Hughes put pressure on, and John de Morgan and several other organisers were charged with incitement to riot (although de Morgan had not even been present after the July 1st events).

There was clear disagreement locally over methods of saving the Common: obviously the more respectable campaigners plumping for legal means and disapproving of the rioting. Local secularist Robert Forder (another defendant in the Riot trial) also bitterly criticised De Morgan, accusing him of pocketing defence funds. He had previous issues with De Morgan from the Irishman’s split with Secularist leader Charles Bradlaugh, who Forder supported.

At the trial, in October 1876 at Maidstone, 3 men including Forder were acquitted, but de Morgan was found guilty. Sentenced to a month in jail, he was unexpectedly released early: a planned 20,000-strong march to demand his release turned into a mass celebration with bands. Effigies of Hughes and Kentish Independent journalist (and later historian of the area) WT Vincent, who had given evidence against de Morgan, were burned on the Common at the Slade. Hughes also sued the liberal Woolwich Gazette and the Man of Kent newspapers for printing de Morgan’s ‘libellous’ speeches.

In the aftermath of the riots, the constitutional campaigners stepped up their negotiations with the Queens College, in an attempt to prevent further rioting. The upshot was that the Metropolitan Board of Works bought Plumstead Common for £16,000, and remains a public open space.

Rob Allen in his “Battle for Plumstead Common” reckons that the local structures of power were undergoing change, and that the struggle over the Common was also a focus for class resentment and other disputes. However, local gentry also opposed the enclosures (while not supporting the rioting) for their own reasons, it was not simply a division along class lines. This can usually be found in many of the anti-enclosure movements mentioned here: they were rarely unified in tactics, or even in their motives for opposition.