Poring and peering. I’ve been poring over old maps a lot recently, and peering over walls and fences and into ditches, trying to understand the relationship between the geology of Shooters Hill and the springs and streams that drain it. My investigation took me down to the Greenwich Heritage Centre, both for their beautiful old geological maps and to read what Colonel Bagnold, David Lloyd Bathe and W.T. Vincent had to say about Shooters Hill springs and geology. The Heritage Centre also has a box of old papers from the 1930s by local geologist Arthur L. Leach which discuss the details of the geology and report his observations.

Why did I start on this? I had noticed that some locations on the hill seemed to be always wet, and small streams sprung from them after rain. Streams that couldn’t be explained by the latest Thames Water leak. For example the woods just up the hill from Christ Church School is one streamy spot, and the steep, stony stretch of Mayplace Lane just above Highview flats another. My curiosity was piqued.

The story of the springs of Shooters Hill goes back to the late 17th century and the area was famous for its mineral wells. Hasted records in his seminal 1797 work “The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent” that there was on Shooters Hill “a mineral spring, which is said constantly to overflow, and never to be frozen, in the severest winters.” In Henry Drake’s 1866 revision this is interpreted as referring to springs in Red Lion Lane, and is expanded to say that the springs were discovered in about 1675 by John Guy and were called the “Purging Wells”. Bagnold reported that these springs were in the garden of 80 Red Lion Lane, and overflowed across the Lane and down to Nightingale Vale. It was visited by people wishing to take the waters up to the end of the nineteenth century. Diarist John Evelyn and Queen Anne were said to have used the Shooters Hill waters, and at one stage there was a grand plan to turn Shooters hill into a spa town.

The chemistry of the Shooters Hill waters was analysed by the Royal Military Academy’s James Marsh, showing that its main ingredient was Magnesium Sulphate, also known as Epsom Salts. These medicinal springs seem to have different geological origins to other springs on Shooters Hill.

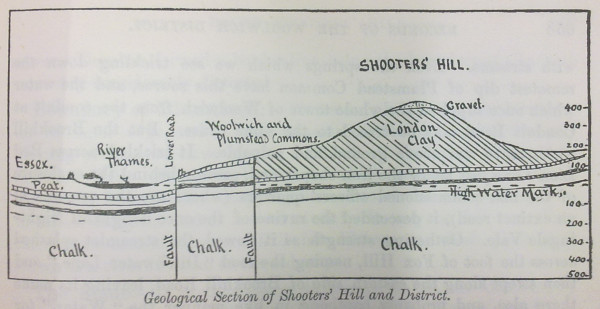

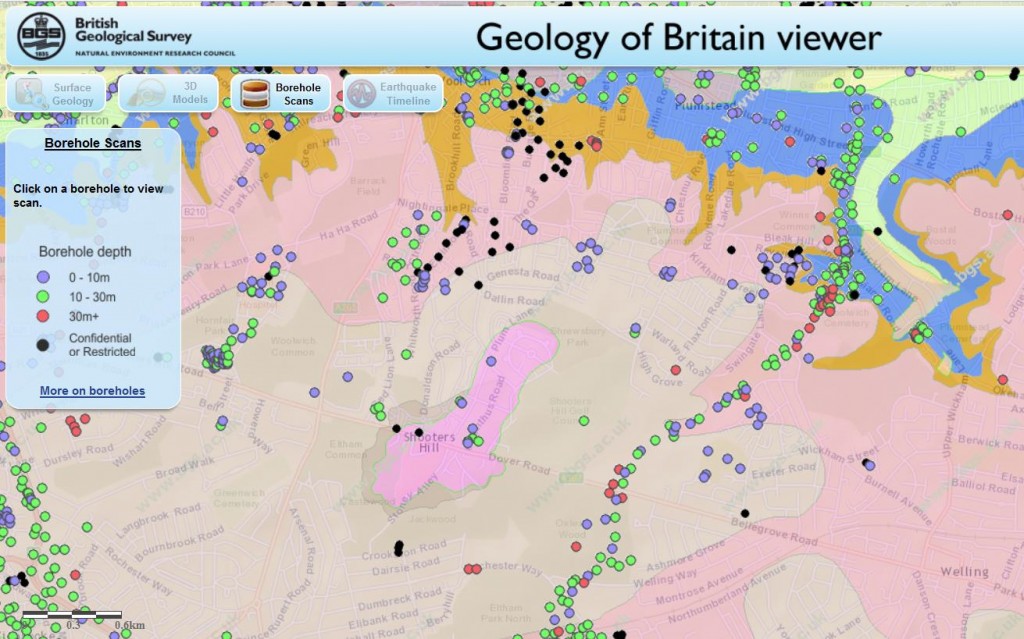

Shooters Hill can be thought of as comprising three geological strata. The bulk of the hill and lowest layer is London Clay. Next is a layer known as the Claygate Beds, which itself is layers of sand and loams with thin bands of clay. On top there is a layer of gravel, known as Shooters Hill Gravel, which Wessex Archaeology describe as “well rounded flint gravel, sandy and clayey in part”. Bagnold describes it as “red, clayey gravel and sands.” It can sometimes be seen when ditches are dug, for example to put down services pipes and cables; there’s a good example at the moment in a fresh ditch by the side of the path leading to Severndroog Castle. The gravel layer is shaped a bit like an irregular doughnut sitting on top of the peak – at the very top of the hill it is very thin or even non-existent and it increases in thickness going down the hill as the Claygate Bed layer drops away more steeply. Leach shows the top surface of the London Clay sloping towards the West-South-West so the Claygate Beds and Shooters Hill Gravel are thicker in the direction of Eltham Common. The gravel is thought to cover an irregular area about a mile long by half a mile wide, as can be seen from the British Geological Survey map extract below.

(As an aside, it has been argued that the geological structure of Shooters Hill, specifically the faults shown in Vincent’s cross-section above, created London.)

The top two layers are porous, and in wet weather retain water, which cannot drain through the impermeable London Clay and so appears as springs at the edge of the upper layers where the clay becomes the surface. The spring above Christchurch school is explained by this mechanism: the BGS map shows that the Claygate Beds layer ends at exactly the point where the spring appears. Bagnold says that up until around the second half of the nineteenth century there was a dipping well at this location, and that it is believed this well was the main source of water for the Shooters Hill hamlet around the Red Lion pub until the Kent Waterworks laid on a water supply.

Other streams and water flows, where maps can be found that show them like Nokia Maps, seem to start from around the edge of the gravel/Claygate layers. For example the origin of ditches on Shooters Hill Golf Course, like the one in the photo at the top, and others in Oxleas Wood seems to lay on the boundary line.

The flow of water in Mayplace Lane is not so easily explained because the map shows that the Claygate Beds layer don’t extend that far and the western boundary of the Shooters Hill Gravel runs parallel to and quite close to Plum Lane. I’m not a trained geologist, but I wonder whether is this is accurate, for two reasons. Firstly the 1866 OS map shows that there was a gravel pit between Eglinton Hill and Mayplace Lane opposite the junction with Brent Road, so there was some gravel that far down the hill, though of course it may have been a pocket of gravel separate from the main layer.

Secondly, Alfred Leach wrote some “Further Notes on the Geology of Shooters Hill, Kent” about his observations of trenches being dug for sewers along Plum Lane from Genesta Road up to Mayplace Lane. Someone else who spent time peering into ditches! He noted that from Dallin Road upwards the trenches passed through sands and pebbles down to London Clay, apart from a few points where the gravel layer went deeper than the 8ft deep trench. That would seem to indicate that the Shooters Hill Gravel extends further north than the BGS map, though Leach thought that undisturbed gravel only extended as far as the midpoint between Furze Lodge and Dallin Road, after that it was gravel that had drifted down the slope. The southern end of Highview flats is on the same 95m contour line as the Plum Lane end of Dallin Road.

It’s a pity the boreholes, shown on the BGS map, that have been used to gather geological evidence don’t cover the North-west of the hill as well as they cover the proposed route of the road to the East London River Crossing through Oxleas Woods and Plumstead.

Most of the streams and springs originating on Shooters Hill have now disappeared – diverted underground or into the drainage system. As long ago as 1890 W.T. Vincent in his Records of the Woolwich District was bemoaning the loss of streams, and mentioned a number of them. There was the Nightingale Brook which sprang from “the swampy waste behind the Royal Military Academy”, then trickled across Red Lion Lane before descending the “ravine of the once delightful Nightingale Vale”, along the eastern side of Brookhill Road down to the Woolwich Arsenal where “it filled a moat about a barbacan, and finally fell into the bosom of Father Thames.” This stream marked the boundary between Woolwich and Plumstead. Another across Woolwich Common marked the boundary with Charlton.

Vincent also believed that Shooters Hill was the source of the River Quaggy, citing springs which rose behind the police station and crossed the Eltham Road under an arched bridge on its way to Kidbrooke. This sounds like the Lower Kid Brook described by the Kidbrooke Kite in his guide to the Kid Brooks. The Kid Brooks were tributaries to the Quaggy.

On the eastern side of the hill the Oxleas Woodland Management Plan says that Oxleas Wood and Sheperdleas Woods drain into the River Shuttle, which is a tributary to the River Cray, and Nokia Maps shows some streams heading in that direction via Rochester way and Falconwood Field. However I was intrigued by what Bagnold said about some other eastward heading streams. These fed into what Vincent calls “An Obsolete River” and the Plumstead River, and Bagnold asserts was once called the River Wogebourne or Woghbourne. I’ll talk more about my efforts to trace this lost river in my next blog post.