Today an email arrived from the admin for a brand new online forum about Shooters Hill. It’s with great pleasure that the link to the site is provided here: http://shootershill.phpbbhosts.co.uk/

Woolwich Riots

Last night there was rioting in Woolwich which culminated in arson attacks on a number of buildings. Surprisingly, there are still a lot of people in the surrounding area who aren’t aware of this, mainly due to the lack of coverage in the mainstream media; Twitter however gave rise to an increasingly heartbreaking series of images during the night, starting from around 8pm, and ending up with those showing the buildings around General Gordon Square in flames. The fire brigade were still fighting major blazes in Woolwich at 3am.

This video shows young people chasing riot police away from General Gordon Square down Thomas Street just after 10pm last night.

Some of the photos posted on Twitter showing the burning police car on New Road, the looting on Powis Street, and the arson attack on the Great Harry Pub.

The twitter reports that are used here came from a number of sources, including mister mercer, jelvesie (who captured the footage above), and dontcallmedick, among others. Although the police have suggested that people shouldn’t observe the riots, there was no press coverage, so citizen reporters were the only source of local info on this terrible night.

The leader of the council has made a statement, in it he restates his commitment to regenerating Woolwich, which has been going well, and this was discussed recently. The leader also insists that he will help the shopkeepers in affected areas, and hold the perpetrators to account.

update 10/8 – here’s a film of the cleanup from yesterday

Green Chained Walk

It doesn’t happen very often, but every now and then a web search leading to the site, or a grumble on twitter indicates that all is not entirely well on the Green Chain Walk through the local area at present, specifically on the section that runs through Woodlands Farm. This may be a temporary difficulty, and it’s not entirely clear at what times the route is being affected.

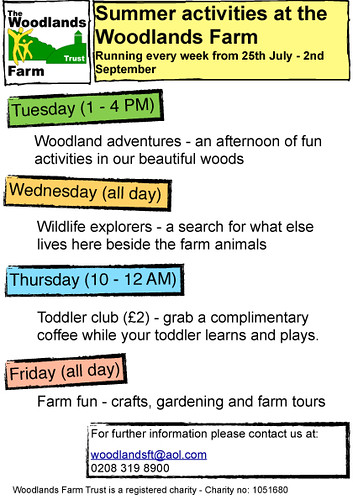

Woodlands Farm Summer Holiday Activities

This latest addition to the farm’s activities for young people began last week, and runs throughout the school holidays.

The Woodlands Farm Trust Summer Holiday Activities 2011

Running Tuesday-Friday every week from 26 July-2 September

Drop-in, no booking required.Tuesdays 1pm-4pm

Woodlands Adventures – an afternoon of fun in our beautiful woods.

Suitable for ages 6-14 (all children must be accompanied). FREE.Wednesdays 10am-4pm

Wildlife explorers – a search for what else lives here besides the farm animals

Suitable for ages 6-14 (all children must be accompanied). FREE.Thursdays 10am-12pm

Toddler Club (n.b. this will continue beyond the summer)

Come and meet the animals, try out arts and crafts, play, and meet up with other families. Tea/coffee

and biscuits provided. £2 per adult, children FREE! Suitable for ages 6 and under (all children must

be accompanied).Fridays 10am-4pm

Farm fun – crafts, gardening and farm tours.

Suitable for all ages (all children must be accompanied). FREE.Farm Details:

The Woodlands Farm Trust

(registered charity 1051680)

The Woodlands Farm Trust

331 Shooters Hill

Welling, Kent

DA16 3RP

Nearest tube: North Greenwich

Nearest BR: Welling

Buses: 486 & 89

Telephone & Fax: 020 8319 8900

Email: woodlandsft@aol.com

www.thewoodlandsfarmtrust.org

pMap

Welcome to pMap (planningMap). It currently offers this service: take the previous 28 days’ planning applications to lbg, map those that can be geo-coded (by postcode), and list those that can’t. You can read a bit more about it and check the source code below.

pMap

A party of women, armed with saws and hatchets

The 1876 riot that apparently saved Plumstead Common from enclosure, in the photo the people are digging up the enclosing fences (apparently).

Having recently run into something of a copyright challenge it was quite nice to pick up a book that has the following announcement inside its front cover: “Please reproduce, spread, use all or part of this text (so long as it’s not for anyone’s personal profit), but we’d like to know you are doing so.” The text that’s about to be reproduced, spread and used on this site was originally put together by past-tense publishing, and investigates a number of historic events connected to the preservation of green space in South London, including the one below: a riot that prevented the enclosure of Plumstead Common.

“A Series of Wild and Violent Riots”

Plumstead Common belonged to the Provost and Scholars of Queens College, Oxford. Freehold tenants had enjoyed rights of cattle-grazing, and collection of gravel, turf, loam etc for centuries. It was a wild and picturesque place, loved by locals, especially kids. Troops had been allowed to exercise here in the 19th Century, leading to “the present ruinous condition of the remoter half” (WT Vincent). In 1816 two plots of land were enclosed where Blendon Road and Bramblebury Road are now. In the 1850s an area between The Slade and Chestnut Rise was sold. There were “distant rumblings” in Parish meetings, but no more. Some small plots enclosed on the fringes of the Common were given to poor widows to keep them out of the workhouse, according to Vincent (more to cut expenses to the ratepayers than from generosity possibly). From 1859 however, the College aggressively pursued a policy of excluding freeholders, asserting they were practically the owners of the waste land. Various encroachments were made, reducing the Common by a third: in 1866 the whole of Bostall Heath and Shoulder of Mutton Green were enclosed.

This led to local outrage, meetings of residents of East Wickham, and the forming of a protest committee, led in March 1866 to the forcible removal of the fences around the Green, and also destruction of fences near the Central Schools around Heathfield and Bleakhill. In a legal challenge by Manor tenants to the College, the Master of the Rolls ruled the enclosures on the Common and Bostall Heath out of order.

“A party of women, armed with saws and hatchets”

‘Illegal’ encroachments continued though – often facing unofficial demolition by locals. The Plumstead Vestry even passed motions in favour of the demolitions! The main targets were the property of William Tongue, a rich local builder who had bought the land here and put fences up, & his crony, magistrate Edwin Hughes, Chairman of the Vestry (later Tory MP for Woolwich). Hughes was said to have “had the key to the Borough in his pocket” -a very powerful man locally. He had bought land off Tongue to add to his garden. Tongue had already been the focus for trouble in 1866 over his enclosing ways. On a Saturday in May 1870, “a number of the lower class, who were resolved to test their rights” demolished fences and carried off the wood. “A party of women, armed with saws and hatchets, first commenced operations by sawing down a fence enclosing a meadow adjoining the residence of Mr Hughes…” Fences belonging to William Tongue were pulled down. There was talk of pulling down Hughes’ house as well. Hughes called the coppers, and some nickings followed. The next day 100s of people gathered and attacked fences put up by a Mr Jeans. When the bobbies arrived many vandals took refuge in the local pubs.

From 1871, the military from nearby barracks took over large sections for exercises and drilling, as Woolwich Common was too small and swampy: the squaddies soon trashed the place, stripping all the grass and bushes and brambles. Protests followed, but nothing changed.

In 1876, Queens College decided to lease the greater part of the common permanently to the army for extensions to the Woolwich Barracks/parade grounds. Local people, including many workers from Woolwich Dockyard, objected to the plans; notices appeared around the town in late June calling for a demonstration. The main organiser of the demo was John de Morgan, an Irish republican & agitator, who had been involved in struggles against enclosures in Wimbledon (in 1875) & Hackney. De Morgan seems to have been a charismatic (or self-publicising) and provocative figure, a freelance editor, orator & teacher, who had been driven out of Ireland for trying to start a Cork branch of the International Workingmens Association (the First International). He had long been a Secularist and Republican, but fell out with some radicals and other Secularists. He had founded a Commons Protection League.

“I Never saw a Scene So Disorderly and Lawless”

On July 1st over 1000 people held meetings in the Arsenal Square and the Old Mill pub, marched up to the north side of the Common (around St Margaret’s Grove) and peacefully tore down fences. Again fences belonging to Edwin Hughes and William Tongue were destroyed – the crowds now had added grudges against them. Both had recently been involved in crushing an 1876 strike by local carpenters and bricklayers over pay and piecework, making then doubly hated. Tongue had brought in scabs to break the strike and Hughes prosecuted strikers for leaving work (under the notorious Employers and Workman’s Act.) A widely disliked Mr Jacobs, who leased a sandpit off the College, also had fences broken.

The following day (Sunday) a crowd returned to demolish the already rebuilt fences: a police attack led to a battle with stones thrown and fires started. Monday saw more rioting: according to a hostile witness there were 10,000 there on Monday and Tuesday, and “I never saw a scene so disorderly and lawless.” The furze on Tongue’s land was set on fire. While the cops brought it under control, enthusiastic meetings continued.

Although many rioters were costermongers, local coalheavers, labourers from the Woolwich Arsenal (700 men took the day off from one department here to hear a de Morgan speech), many more ‘respectable’ workmen were up there trashing the fences.

Hughes put pressure on, and John de Morgan and several other organisers were charged with incitement to riot (although de Morgan had not even been present after the July 1st events).

There was clear disagreement locally over methods of saving the Common: obviously the more respectable campaigners plumping for legal means and disapproving of the rioting. Local secularist Robert Forder (another defendant in the Riot trial) also bitterly criticised De Morgan, accusing him of pocketing defence funds. He had previous issues with De Morgan from the Irishman’s split with Secularist leader Charles Bradlaugh, who Forder supported.

At the trial, in October 1876 at Maidstone, 3 men including Forder were acquitted, but de Morgan was found guilty. Sentenced to a month in jail, he was unexpectedly released early: a planned 20,000-strong march to demand his release turned into a mass celebration with bands. Effigies of Hughes and Kentish Independent journalist (and later historian of the area) WT Vincent, who had given evidence against de Morgan, were burned on the Common at the Slade. Hughes also sued the liberal Woolwich Gazette and the Man of Kent newspapers for printing de Morgan’s ‘libellous’ speeches.

In the aftermath of the riots, the constitutional campaigners stepped up their negotiations with the Queens College, in an attempt to prevent further rioting. The upshot was that the Metropolitan Board of Works bought Plumstead Common for £16,000, and remains a public open space.

Rob Allen in his “Battle for Plumstead Common” reckons that the local structures of power were undergoing change, and that the struggle over the Common was also a focus for class resentment and other disputes. However, local gentry also opposed the enclosures (while not supporting the rioting) for their own reasons, it was not simply a division along class lines. This can usually be found in many of the anti-enclosure movements mentioned here: they were rarely unified in tactics, or even in their motives for opposition.

Adair House

It’s not entirely certain what it is about Adair House (opposite the Herbert Pavillions) that makes it so popular with potential Free Schools, but not only are Shooters Hill Primary School of Arts interested, but as of this May they have a competitor in the shape of South London Free School. The executive head of the former indicated recently that they were no longer considering that site, and are now looking elsewhere for a home, so it remains to be seen how the South London Free School will fare in their ambitions to move in…their website has been quiet since May, so perhaps that scheme has gone the way of the fairies?

In any case, Adair House is currently empty, having previously been a hostel, and is owned by the council.

The Secret Market

If you’re looking for something to do tomorrow, there may still be a chance to see the Secret Market, a play put on by Greenwich Theatre in Oxleas Woods. Allocating free tickets significantly reduced the scope of the production (no effects, no musicians, minimal scenery and props), but the production nonetheless comes close to filling the large shoes left vacant by London Bubble, who appear to have been a casualty of the cuts in the Arts Council portfolio, yet have become much loved for turning South East London’s green spaces into a roving auditorium.

One good thing about the show is that incorporates the castle, which it is pleasing to report has recently moved a step closer to being re-opened to the public. Whilst it may still be a short while before the restoration begins in earnest, it’s still encouraging to hear on the grapevine that things are coming along, and the trust, council, and heritage lottery fund are working together towards one goal.

Edmund John Niemann

The your paintings archive, which is bringing together digital photos of the entire national collection includes one of Shooters Hill.

At a guess it was painted from the viewpoint of the Tarn in Eltham, or more likely the River Quaggy. Oxleas Meadow is clearly visible, and the hilltop appears more prominently than it does today, presumably due to the deforestation and gravel quarrying that has taken place since. Originally, the crest of the hill lay where the flats in the Cleanthus Road estate back on to Eaglesfield Park, which is itself now the highest point on the hill.

If by some stroke of luck you find yourself near Glasgow Museums, why not pop in and see if they have it on display?

Shooters’ Hill, Kent

by Edmund John Niemann

Date Painted: 1866

Oil on canvas, 63.5 x 115.6 cm

Collection: Glasgow Museums

Living Streets: The Local Joke

Today a campaigning organisation called Living Streets sent in an email asking for the site to draw attention to the problems that can occur when useful community services are replaced with ones that are arguably less so.

Recently during a discussion on the 853blog about the future of Woolwich, the topic of the conversion of the Woolwich Equitable building (built in 1935) into a Bookies shop led to the revelation that Banks and Bookies fall into the same class with regard to planning, making it relatively easy for Bookies to move in to High Street locations. This may not immediately seem like such a threat to Woolwich, but in Deptford bookiefication has become a phenomenon, and at the last count it was observed that their high street had eight bookies. At a time when Woolwich is rediscovering its sense of civic pride, it could do well to avoid a similar invasion, although the Powis street pedestrian precinct is currently bookie free.

The campaign is promoting a greater say for communities in how changes in the use of public buildings are agreed, and in particular they are hoping to persuade the Secretary of State for Communities to reconsider proposals to further reduce the protections offered by national planning guidelines. As an aside, the proposed changes will also relax planning requirements for things such as preserving historical features, conducting archeological surveys, and protecting views – which is possibly going to be an issue when Furze Lodge is extended upwards.

The campaign is called the Local Joke, and adds to ongoing work on pedestrian safety carried out by Living Streets.